Neivamyrmex nigrescens, Arizona

Army ants have a decidedly tropical reputation. The term conjures spectacular images of swarms sweeping across remote Amazonian villages, devouring chickens, cows, and small children unlucky enough to find themselves in the path of the ants. Of course, the habits of real army ants are not nearly so sensational, but they are at least as interesting.

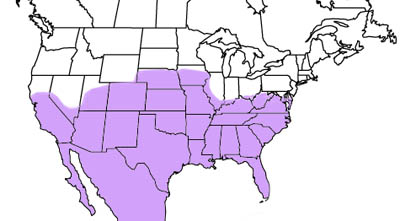

The approximate range of army ants in North America.

Few people are aware that more than a dozen army ant species are found in the United States. Most belong to the genus Neivamyrmex, a diverse group that extends from Argentina to as far north as Iowa. Their colonies are populous, comprising tens of thousands of individuals, and like all ants, theirs are composed largely of sterile female workers, a single reproductive queen, and on occasion winged males for dispersing the colony's genes.

As Neivamyrmex is a true army ant, colonies do not make permanent nests. Instead, the ants rove across- and under- the landscape, making temporary bivouacs out of their own bodies but never lingering for more than a few weeks.

Their prey is other ants. Neivamyrmex is highly specialized for finding and exploiting nests of other ant species. Unlike some of their famous tropical cousins, they do not form diffuse swarms but instead organize their foragers into tight columns. This way they concentrate their forces into a single point, ideal for overwhelming the guards of their target nests.

The photo essay below documents some of the drama, and some of the biology, of the most northerly of the army ants.

A subterranean column of Neivamyrmex californicus near San Francisco, California.

Army ants are found in many habitats, but they are particularly abundant in open woodlands such as this mid-elevation oak savanna in Arizona.

Neivamyrmex can be recognized by their short, thick first antennal segments- the sort that can't easily be chopped off during fighting-Â and by their very small eyes.

A Lasius ant queen is killed by a marauding underground column of Neivamyrmex nigrescens in southern Arizona.

Neivamyrmex californicus workers immobilize a pavement ant during a raid in northern California.

The targets of army ant raids are the protein-rich larvae and pupae, which a successful raiding party will carry off by the thousands.

This Neivamyrmex nigrescens has paralyzed a much larger Aphaenogaster ant and is dragging her off to the bivouac. Army ants typically carry prey slung beneath their bodies, an unusual habit for ants.

Not all ants are helpless in the face of an army ant raid. Here, a Pheidole soldier (top) dispatches attacking Neivamyrmex opacithorax at the colony entrance near Austin, Texas.

Army ant queens (in this case, Neivamyrmex opacithorax) are large insects specialized for laying eggs.

Few non-entomologists will recognize male Neivamyrmex as being ants. These sausage-shaped insects fly about searching for colonies in which to land, drop their wings, and mate. This N. harrisi male was attracted to a light trap in southern Arizona.

Temperate army ants, like their tropical cousins, build bridges with their bodies. Here, a pair of Neivamyrmex melanocephalus initiate a bridge while a third climbs aboard.

Webliography:

Roy and Gordon Snelling's 2007 taxonomy of North American Neivamyrmex

ArmyAnts.org: Gordon Snelling's New World Army Ant Site

Neivamyrmex photos at myrmecos.net

- Log in to post comments

Nice series of photos!

The prey slung under the body looks similar to the way I've seen sphecid wasps carry paralyzed caterpillars.

regards -- ted

Amazing stuff!

Hi Alex, keep up the great blog! My dissertation would be next to impossible without the help of Neivamyrmex [http://www.insectscience.org/8.71/].

Thanks guys!

Adrian- thanks for pointing out your research. I remember trying the army ant trick on a captive colony of Pheidole when I was living in California. The sudden evacuation response was unforgetable, it's great to see that you've found a practical application for it.

Adrian: that is so incredibly cool, using the army ants like your dogs to flush the prey. It's got a hallmark of brilliance: its stunning obviousness once someone else has first pointed it out.

On a related note -- I too was once an ant-enthused kid (see http://myrmecos.wordpress.com/2008/12/08/alex-collects-ants/) but I can't find a cool picture like his).

On summer day during my nineth year, I started to put one citronella ant - Lasius(Acanthomyops) - worker every few seconds down the nest entrance of a small Formica fusca colony. After putting in only about ten of these aromatic yelllow ants, the larger black species' entire colony of 100 or so members was flushed out and ran off into nearby grass.

Also, I have observed that some species of Formica flushed out by Polyergus raids, though others simply hunker down inside the nest while the raiders bully their way about the place. More on this in my (eventually) upcoming revison of Polyergus...

great information, very very interesting. Keep it up. Nice photos