[This past fall, I taught a course at Emerson College called "Plagues and Pandemics." I'll be periodically posting the contents of my lectures and my experiences as a first time college instructor]

Most of this post was written back in September, when it still seemed possible that I would be able to teach the class, write the blog and do science. Please forgive any anachronisms that I failed to purge.

Last time, I talked about what science is and why it's awesome. This is the first half of lecture 2, which was originally given on 11 September, 2012.

Lecture 2a (reading: Zimmer - The Tangled Bank, chapters 1-2 and chapter 5)

In 1650, Bishop James Usher of the Church of Ireland made one of the earliest recorded attempts at determining the age of the earth. By tracing the genealogies of the Old Testament ("Abraham begat Isaac; and Isaac begat Jacob; and Jacob begat Judas and his brethren..."), and cross referencing events in the Bible with other ancient sources, he determined that the earth had been created on October 23rd, 4004 BC at around noon. That's some remarkable precision considering the dubious nature of his source material (as far as I know, he did not include an estimate of error), but we now know that he was off by several billion years.

Another part of pre-Renaissance European thinking that was ripe for challenge was a hierarchy of existence known as the "Scala Naturae," which literally translates to the ladder of nature, but is often referred to as the Great Chain of Being.

1579 drawing of the Great Chain of Being from Didacus Valades, Rhetorica Christiana. Source: wikipedia

This concept, cribbed from Greeks like Aristotle and Plato, placed everything in existence onto a rung in the ladder, from the lowest forms (earth, rocks and minerals) up through plants and animals to the the highest form (God). Each of these rungs could be further subdivided (iron is a lesser mineral than gold, though neither is as high as the lowest plant etc), and one of the defining features of your position in this chain of being was that it is unchanging. Plants don't become animals, and serfs don't become kings (of course, there was political advantage in people believing that their station is fixed and ordained by God, but that's a conversation for another time).

Both of these notions - the young Earth and the fixed nature of Creation exemplified by the Scala Naturae - began to come under fire in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, when people started actually observing the things around them in a systematic way. Early geologists started to work out the processes by which sediment could turn to stone, and came to understood that the geologic features they observed could not have happened in 6000 years, or even in 60,000 years. By the mid 19th century, it was generally accepted by learned people that the Earth had to be at least millions of years old, if not tens of millions of years old.

In addition, these same geologists were finding fossilized creatures in the rock that were quite different from the forms of animals that they knew, and others that resemble modern forms, but were found in strange places (seashells atop mountains for instance), and they began to suspect that something wasn't quite right about the conventional wisdom. Of course, there were those that tried to explain away these observations by invoking catastrophes like floods, earthquakes and volcanoes, but it became increasingly clear that the living world was also in a state of flux.

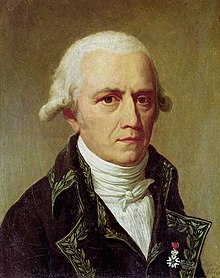

These days, the notion of evolution is almost entirely associated with Charles Darwin, but Darwin was not the first person to come up with the idea - not by a long shot. The notion that organisms could change over time, and the mechanism by which they did so was being seriously debated for decades before Darwin. One of the most well known attempts at a mechanism was from Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, who hypothesized that organisms were constantly struggling to improve themselves in their own lifetimes, and then pass the results of that struggle on to their offspring. In other words, Lamarck's idea suggested that if I do a lot of yoga and weight-lifting, my children will be stronger and more flexible. This idea is a bit reminiscent of the Scala Naturae; organisms in Larmarck's view were always striving towards perfection (striving to climb the ladder of nature).

Jean-Baptiste Lamarck - Source: wikipedia

We now know that Lamarck's mechanism is not true - experiences of a parent do not affect their offspring (with a few notable and quite interesting exceptions) - but even the correct mechanism of natural selection did not originate with Darwin. Edward Blyth, a staunch creationist theologen, hit upon the notion of natural selection as a way of pruning out the weak and deteriorating members of a species - thus preserving God's creation (what we would now call stabilizing selection). In 1831 (the year Darwin left on the famous voyage of the Beagle), the shipwright Patrick Mathew published a hypothesis about a force like natural selection as a means by which species could change, but he only devoted a couple of paragraphs to the idea and buried it in an appendix on a book about growing the best trees for ship-building lumber.

Darwins principal contribution, and the reason his name became synonymous with the theory of evolution, was the shear weight of his argument. On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life is staggeringly complete, and breathtaking in its attention to detail. When I read it for the first time, I was shocked at how many modern creationist tropes, from "irreducible complexity," to the evolution of the eye, to the idea that evolution would take too long, are brought up by Darwin himself and then meticulously refuted. Though our understanding of biology has advanced considerably in the last 150 years, Darwin didn't even need to know about genetics to get the basic story correct.

In addition, Darwin didn't just make observations and then propose a potential explanation, he also did experiments. For instance, he knew that in order for life to arrive on volcanic islands, it would need to get their from the mainland, but no one knew if this was possible. Darwin collected seeds from around his home in England and then dropped them in a bathtub of salt water for different lengths of time, noting that many floated and could germinate after extended periods of soaking. The technology for extracting the genetic material of an organism and sequencing it in molecular detail is now available in just about every biology lab in the world (and all supports Darwins original theory), but Darwin did the experiments that he could do in order to lend support to what is now the foundation of our biological understanding.

So what was the theory? Those of you that read a lot of science blogs might have a more sophisticated understanding of evolution, but the core ideas of Darwins theory were Common Ancestry and Descent with Modification. Crucially, the mechanism that enabled decent with modification to produce the myriad of modern species from a common ancestor is Natural Selection. Darwin (and most naturalists at the time) knew that there was variation within populations. Further, they knew that this variation could be passed down to offspring. Animal breeders had known this for millennia, and had been artificially selecting animals by breeding pairs of animals with desirable traits for many generations. Darwin observed that incredible differences between different pigeon breeds, which were documented as arising from a common ancestor, could arise because of artificial selection, surely the struggle for living in the natural world could also lead to profound changes.

The Need for Genes

Darwin was able to refute many of the potential criticisms of his theory, but one problem continued to dog him and his supporters: how could new traits arise in a population? Selecting among variation already present in a population is all well and good, but in order to hypothesize common ancestry, Darwinian theory would need a mechanism by which new variation could spread throughout a population. Breeders knew they could select and amplify traits, but they believed that these traits were determined by some quantifiable substance that was mixed during each generation. If something brand new appeared, it would necessarily be diluted out in future generations, like a drop of dye in a lake full of water.

That all changed when a fastidious German monk started growing peas.

Up next: Lecture 2b - Genes, traits and the Central Dogma

- Log in to post comments

I've taught an evolution course at the undergraduate junior level a number of times. I like what you have done so far.

Evolution is so cosmic that it is difficult to address. How much do we discuss the history of the idea? How much on the history of life? How much on experiments and observations? How much on genetic level processes? How much on population genetics? Phylogeny, systematics and taxonomy? And then a bit on creationism and ID to top it off?

Thanks Jim.

I think it really depends on the students that you're teaching, and what the focus of the class is. For the students at Emerson, I tried to include as much history as possible, and they seemed to respond to the stories more than anything else. They're not science majors (for most of them, this will be the only science class they take in college).

My hope was to dispel some of the misconceptions about how evolution works, and give them enough of a foundation to understand the evolution of pathogens (since that is what the class is about), without overwhelming them with mechanism. I'm not sure I succeeded... I think it will take a couple of iterations before I'm really good at this.