metabolism

Image of a genetically obese mouse (left) from Wikipedia.

To deal with cold environments, mammals have several options. They could produce heat by increasing metabolism or shivering or they could conserve heat by constricting blood vessels in their skin or snuggling with a friend or insulating materials. With this in mind, researchers wondered how varying levels of insulation (obesity, fur) in mice affected heat loss and how much energy the animals used to maintain body heat. Their thinking was that more insulation would prevent heat loss and lower energy…

Cells that “spit” out their contents and messenger RNA that is not so swift at delivering its message. Those are two brand new stories on our new and improved website. Check it out and let us know what you think.

The first story arose from a simple question: How do secretory cells – those that produce copious amounts of such substances as tears, saliva or all those bodily fluids – manage to get their contents out of the cell? Cells are walled all the way around; they don’t really have doors for letting things the size of a drop of fluid out. Instead, they use the vesicle system – small globes…

If you happen to be in the Arctic this summer polar bears (Ursus maritimus) can be spotted spending their time on the sea ice or on the shore in areas where ice has melted. While it is difficult to study the physiology of bears living on the ice, it had been hypothesized that bears living on shore experience a state similar to winter hibernation in which they attempt to decrease their energy expenditure when food resources are low. However, new research published in Science shows that bears living on the ice as well as those on shore experience some decrease in activity as well as body…

Image of Gould's long-eared bat from http://www.wiresnr.org/Microbats.htmlImage by: Lib Ruytenberg

I came across a neat study published recently in the American Journal of Physiology - Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology which examined how bats arouse from hibernation, a period during which their body temperature and metabolism are low. To minimize the high energetic costs of warming up during arousal, bats use solar radiation or take advantage of fluctuations in the ambient temperatures (i.e. environmental).

Researchers studied hibernating long-eared bats (Nyctophilus…

In a phenomenon known as Peto's paradox, large mammals do not develop cancer more often than small mammals, despite having more cells that could go haywire. On Life Lines, Dr. Dolittle writes "Some researchers suggested that perhaps smaller animals developed more oxidative stress as a result of having higher metabolisms. Others proposed that perhaps larger animals have more genes that suppress tumors." But a new hypothesis argues that large mammals have evolved to minimize the activity of ERVs, which are ancient viral elements integrated into our DNA. Active ERVs can cause cancer and possibly…

Image of eyeless Mexican tetra fish from www.seriouslyfish.com by H-J Chen.

The metabolism of most animals follows a circadian rhythm that differs between the day and night. Mexican cavefish living in constant darkness, lost this circadian rhythm some time ago. In a newly published study in PLOS ONE, researchers compared the metabolic rate of both cave- and surface-dwelling Mexican tetra fish (Astyanax mexicanus). They hypothesized that since the fish living in each location naturally experience differences in food, predation as well as exposure to daily light fluctuations, they might also…

Scientists use a 'gene gun' to insert a gene from a flowering plant called rockcress into the cells of wheat seeds. The genetically modified wheat became more resistant to a fungus called take-all, which in real life can cause "a 40-60% reduction in wheat yields."

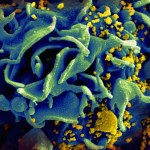

T-cells from six HIV+ patients were removed from their bodies, treated with a zinc-finger nuclease designed to snip a gene out of the cell's DNA, and put back in the patients. Removal of the gene mimics a naturally occurring mutation which confers resistance to the HIV virus. But only 25% of the treated cells showed evidence of…

Image of a great white shark from Wikimedia Commons.

Dr. Michael Stanhope from Cornell University has discovered that great white sharks actually share more proteins involved in metabolism and biochemistry in common with humans than zebrafish, a common fish model used in biomedical research. They made this discovery by sequencing the transcriptome of a heart isolated from a great white shark. I find it fascinating that sharks have more proteins in common with mammals than with bony fish, even though sharks and bony fish are not very closely related.

Source:

Cornell University Press

Dr. Dolittle spent a few days at the Experimental Biology meeting of the American Physiological Society, learning incredible facts about animal adaptability. In the Sunday session, researchers showed that metabolic byproducts called ketones can protect against seizures caused by hyperbaric oxygen therapy, while seal pups, who fast for up to three months once weaned, increase their insulin resistance and become effectively diabetic. Monday taught us that insects lack lungs, instead exchanging gas through tiny valves called spiracles along their abdomen, while a Burmese python, after eating a…

Last time I told you about how the view of cancer switched from the perspective of metabolism to oncogenes. Today we'll see how recent developments have placed the spotlight back on metabolic pathways.

I'll begin this tale with a quote from a review written by Andrew M Arshama and Thomas P Neufeld:

The TOR (target of rapamycin) signaling pathway has been the subject of a 30-year-long reverse engineering project, beginning in the 1970s when the macrocyclic lactone antifungal compound rapamycin was purified from soil bacteria found on the Pacific island of Rapa Nui, famous for its moai (giant…