![]() Using genetic engineering, a group of scientists have developed a way of sneaking a virus past the brain's defences. Don't panic - this isn't some nightmare scenario. It could be the first step to curing a huge number of brain diseases.

Using genetic engineering, a group of scientists have developed a way of sneaking a virus past the brain's defences. Don't panic - this isn't some nightmare scenario. It could be the first step to curing a huge number of brain diseases.

The brain seems incredibly well protected amid its shell of bone and cushioning fluid. But even the strongest of forts needs supply lines, and brain is no exception.

The brain seems incredibly well protected amid its shell of bone and cushioning fluid. But even the strongest of forts needs supply lines, and brain is no exception.

A dense network of blood vessels carries vital oxygen to its cells. These vessels are a potential vulnerable spot, providing access for bacteria and other disease-causing organisms to migrate in from other body parts.

But even these weak spots are heavily guarded. The blood vessels in the brain are lined with a tightly packed layer of cells that restrict the flow of molecules from blood to brain. These cells form a protective shield called the blood-brain barrier, or BBB.

It is a superb defence but it can do its job too well. Not only does it block out dangerous microbes, but it can also exclude large proteins and drugs designed to treat brain diseases. Usually, these large molecules need to be distributed throughout the entire brain to be effective. With the BBB in the way, they don't stand a chance. Now, Brian Spencer and Inder Verma from the Salk Institute of Biological Studies have come up with a way to disguise helpful molecules to sneak them past the brain's defences

Their method exploits special gates in the barrier that control the import of essential nutrients and molecules like cholesterol into the brain. These molecules are escorted by a large protein called apoliprotein B (apoB), and are presented to sentinel proteins that guard the gates.

One of these guardians, called LDLR, is designed to recognise a specific segment of apoB. Once it has confirmed the visitor's identity, it escorts apoB and the molecules it accompanies through the barrier. The whole system works with the tight control of a maximum security prison.

Spencer and Verma managed to fool the system. They took the part of apoB that is recognised by LDLR and stuck it to various proteins, giving them the molecular equivalent of a fake pass.

First, they tested their method in mice. They injected the animals with a harmless virus designed to travel to its liver and spleen. There, the virus sets about building the disguised protein, which is secreted en masse into the bloodstream.The beauty of this method is that it works after a single injection that transforms the liver and spleen into factories for the protein of choice.

Their first candidate was GFP, a jellyfish protein that glows in the dark with a greenish hue, allowing it to be easily tracked. Sure enough, the injected mice soon gave off a greenish glow from their brains and the rest of their central nervous systems.

Their first candidate was GFP, a jellyfish protein that glows in the dark with a greenish hue, allowing it to be easily tracked. Sure enough, the injected mice soon gave off a greenish glow from their brains and the rest of their central nervous systems.

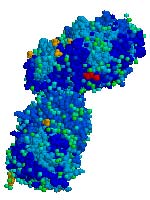

Better still, their method showed real practical potential by sneaking an enzyme called glucocerebrosidase (right) into the brain. Glucocerebrosidase is vital for the storage of fats. People who lack it suffer form a condition called Gaucher's disease, where fatty desposits collect on various organs and cause brain damage, among other symptoms.

The disease is relatively easy to fix using regular injections, but the resulting brain damage is not for the injected enzyme is usually repelled by the blood-brain barrier. But Spencer and Verma's method may change all that.

The duo fully admit that their work is merely a first step, but it is an important one nonetheless. The technique must first be refined and tested in people before it can be widely used. Developing drugs and proteins for treating brain disorders is pointless if those new medicines just congregate uselessly outside the blood-brain barrier. Spencer and Verma may have given them a way in.

Reference: Spencer & Verma. 2007. Targeted delivery of proteins across the blood-brain barrier. PNAS 104: 7594-7599.

- Log in to post comments

I realize these question may instantly out me as a complete layperson, but there are some things I'd really like to know about this:

- What are the indicators that enable the researchers to understand, predict and control how strong the impairment of the normal biological function of these organs is?

-Woudn't they need to be able to control the amount of protein built and released as well as the ovarll duration of viral infection in order for the treatment to be of any real use? Or does the structure of the chosen virus (given a specific immune-system) determine all this and thus enable the researchers to 'tune' the relevant parameters?

Best,

-Mike