tags: blue tit, Cyanistes caeruleus, extrapair fertilization, genetic benefit hypothesis, genetic similarity, plumage color, birdsong, ornithology, behavioral ecology

Even though most bird species form social bonds with their mates, they are not always faithful partners to each other. It's easy to figure out why male birds engage in extrapair copulations: this increases the total number of their offspring -- and this increases their reproductive fitness. But since female birds are physically capable of producing only limited numbers of offspring per breeding season, why would they seek out extrapair copulations? How do they benefit?

According to the most commonly accepted explanations for this behavior, it is thought that female birds who mate with more than one male benefit directly by safeguarding against the potential infertility of her mate or indirectly in one of two ways: the female might be seeking out males with genes that are superior to hers and especially to those of her social mate as the father her chicks (the "good genes" hypothesis); or the female may be seeking unrelated males to increase the genetic diversity of her offspring or to avoid inbreeding depression (the "complementary genes" hypthesis). However, these two hypotheses are not mutually exclusive and further, the data generated by previous studies do not provide clear support for either of these hypotheses, so a group of scientists from the Laboratoire des Sciences de l'Information et des Systèmes designed a series of experiments to learn which hypothesis is most correct.

To do their research, the team studied a population of blue tits nesting in an area that contained 1000 nestboxes over two years. Blue tits, Cyanistes caeruleus, are common garden birds throughout most of Europe. These sedentary monogamous birds feed from backyard birdfeeders and readily utilize human-made nestboxes, and thus, because of their relative ease around humans, they are easy to study.

The first experiment that the team designed was a test of the "good genes" hypthesis. In short, the researchers asked if the female's body condition and that of her social mate influenced whether she sought out extrapair copulations. To answer this question, the team measured the female's body condition by capturing and weighing her daily, beginning six days before she laid her first egg until after she had laid her sixth egg, and they measured the male's sexual displays while the female was in her fertile period by recording and analyzing several variables of his dawn song performance and by plucking several feathers from his crown while he was raising chicks and measuring four plumage color variables.

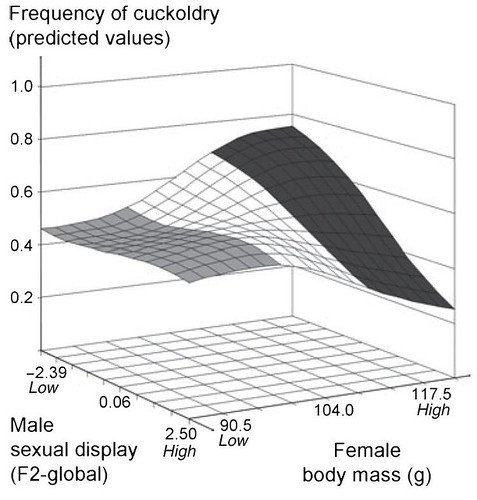

When the team analyzed these data, they found that female blue tits were more likely to produce extra-pair young (EPY) when two conditions were met: first, these unfaithful females enjoyed better-than-average body condition and their mates produced a less conspicuous dawn song display than average, indicating that they were high-qiality females who had "settled" for a low-quality mate (figure 1);

Fig. 1 Probability of occurrence of extrapair fertilization in female blue tits as a function of female body mass and male sexual displays (F2-global) (predicted values). Heavy females (dark grey) had a higher probability of producing extra-pair young (EPY) when mated to males with less conspicuous display (df = 17, χ2 = 7.84, P = 0.0051, n = 19), while leaner females (white and light grey) did not (df = 50, χ2 = 0.01, P = 0.94, n = 52). The interaction between female body mass and male sexual display was significant (df = 1, 57, χ2 = 6.33, P = 0.012; see Table 3 [not shown]).

DOI: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01578.x [larger view].

As expected, the team found that these high-quality females who settled for low-quality mates (as determined by poor song performance and less plumage brightness) were more likely to seek out extra-pair fertilizations and their EPY were larger than their within-pair young (WPY), a finding that supports the "good genes" hypothesis.

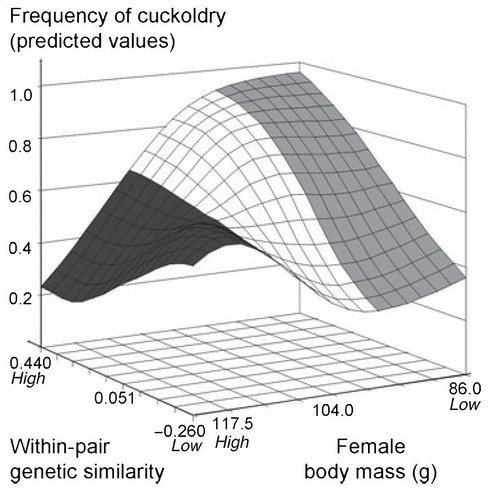

The next experiment that the team designed was a test of the "complementary genes" hypthesis. In short, the researchers asked if the female's body condition affected the number of EPY that she produced if she and her social mate were closely related. To answer this question, they analyzed the genetic similarity of five variable microsatellite loci in the genomes of the adult birds and in their chicks. Genetic similarity was assessed and numerical values ranging from -1.0 to 1.0 were assigned by a computer program. Using this program, the genetic similarity of two individuals that share the same parents will be described numerically as 0.5, while the relatedness of two individuals that share just one parent will be 0.25 (figure 2);

Fig. 2 Probability of occurrence of extrapair fertilization in female blue tits as a function of female body mass and pair genetic similarity (predicted values). Lean females (light grey) had a higher probability of producing EPY when mated with genetically similar males (df = 26, χ2 = 7.30, P = 0.007, n = 28), while heavier females (white and dark grey) did not (df = 58, χ2 = 0.77, P = 0.38, n = 60). The interaction between female body mass and pair genetic similarity was significant (df = 1, 57, χ2 = 12.08, P = 0.0005; see Table 3 [not shown]).

DOI: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01578.x [larger view].

According to these data, low-quality females, as identified by their lean body masses, were more likely to produce EPY when they were closely related to their social mates than were high-quality females, thereby producing more heterozygous extrapair chicks. In short, these data support the "complementary genes" hypthesis.

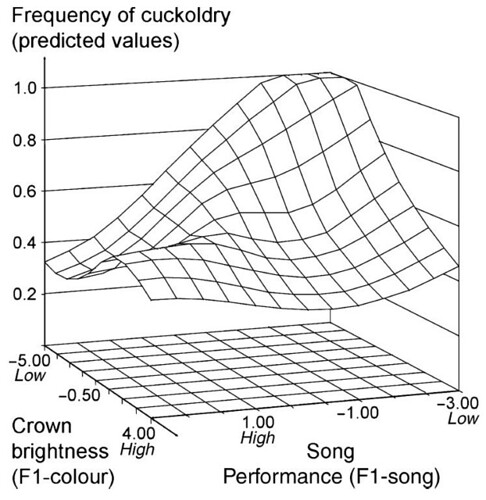

But which of the males' sexual signals -- song performance or plumage brightness -- were the most important indicators of male quality? The team combined the parameters measured for each sexual signal into one character and then analyzed both characters to gain insight into how female blue tits were assessing their mates' quality and how they were using that information to decide whether to seek extra-pair copulations (figure 3);

Fig. 3 Probability of occurrence of extrapair fertilization in female blue tits depended on the interaction between two male secondary sexual characters (song performance (F1-song) and crown brightness (F1-colour); df = 1, 66, χ2 = 5.99, P = 0.014, n = 71) (predicted values). Males with two low conspicuous signals lost more paternity than males with two highly conspicuous traits.

DOI: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01578.x [larger view].

According to their data, the team discovered that plumage brightness and song performance were not correlated, but they found that both song performance and plumage brightness were important to female blue tits, and that males with poor song performance and dull plumage were most likely to be cuckolded by their mates. Interestingly, previous research suggested that crown plumage color might be correlated with heterozygosity, although this study did not confirm this work.

As you might have noticed, the researchers used multidimensional analyses -- those funky graphs -- to present their data. In their paper, they make a strong argument for the utility of this approach when identifying and analyzing the subtleties of reproductive behavior.

"Our results highlight the necessity of multi-dimensional approaches to investigate the complexity of sexual behaviour," write the authors. "In this study, a clear pattern appeared when both male colour and song were entered in the analysis, and when taking female phenotypic characteristics into account. Only accounting for a single secondary sexual trait at a time may prevent us from detecting relationships between male traits and probability of extrapair fertilization, if females and competitors use multiple traits to assess male quality, or if individuals adopt different strategies or are under different constraints depending on their own condition."

These research data suggest that mating patterns in animals may actually be condition dependent. In blue tits, female body mass affected the type of extrapair genetic benefits obtained when they raised EPY, and multi-dimensional analyses appear to be a powerful way to discover these different reproductive strategies.

Source:

A. N. DREISS, N. SILVA, M. RICHARD, F. MOYEN, M. THÃRY, A. P. MÃLLER, Ã. DANCHIN (2008). Condition-dependent genetic benefits of extrapair fertilization in female blue tits. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 21 (6), 1814-1822 DOI: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01578.x.

- Log in to post comments

The heck with the fidelity issue. Why are they called blue tits when they're actually yellow?!!!

Let's get Sarah Palin to get us an earmark to study this!

They're only yellow on the outside.

Don't know if it is relevant but have a nesting box in the garden [Scotland] that has three adults feeding the chicks [now on their second clutch].

Don't know if it is relevant but have a nesting box in the garden [Scotland] that has three adults feeding the chicks [now on their second clutch].