tags: teratornis, Argentavis magnificens, birds, ornithology, giant bird

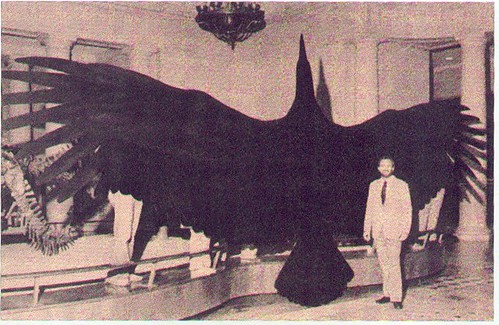

Dr. Kenneth E. Campbell, (one of the discoverers) in front of the 25 ft. wingspan Argentavis magnificens. Display from the Natural History Museum, Los Angeles. The feather size from such a bird is estimated to have been 1.5 meters long (60 inches); and 20 centimeters wide (8 inches). [larger]

Image source.

Discovered decades ago and formally described in 1980, Argentavis magnificens is the largest bird known. It lived six million years ago during the Miocene period throughout Argentina. It is nearly the size of a Cessna 152 light aircraft, with a 23-foot (7-meter) wing span and weighing approximately 150-pounds (70-kilograms). However, even though this bird's muscles were well-developed, they still were not sufficient to generate enough lift for the giant bird to leave the ground. So how did this, the largest of all birds, fly?

Paleontologists have scratched their collective heads over this question for decades, although at least a few of them suspected that the bird soared.

"Takeoff capability is the limiting factor for the size of flying birds, and Argentavis almost reached the upper limit," said Sankar Chatterjee, a professor of geosciences and curator of paleontology at the Museum of Texas Tech University, and lead author of the newly published paper.

In a new study, an unusual collaboration between Chatterjee and his colleague, Kenneth Campbell, with a retired aeronautical engineer, Jack Templin, they confirmed that the now-extinct Argentavis magnificens was actually a high-performance glider, soaring on thermals and updrafts just as vultures and birds of prey do now.

To carry out this research, the scientists used flight simulation software to learn more about the ancient bird's flight parameters by providing it with the dimensions of the bird's bones. This analysis revealed that Argentavis magnificens, similar to most large soaring birds, was too large to sustain powered flight, but could soar efficiently, reaching speeds of up to 67kph (41mph) under the right conditions.

Apparently, Argentavis relied on updrafts in the foothills of the Andes, known as thermals, which are columns of heated air that are deflected upward over a ridge or a cliff. Thermals provide lift for small aircraft as well as for soaring birds, such as modern-day condors, eagles and storks. It's likely that Argentavis circled upwards on a thermal and then soared from one thermal to another over long distances in what the researchers refer to as "slope soaring". Even though the bird's huge wingspan gave it a 100-foot turning radius, this was small enough that it could continue circling within a thermal as it rose high above the plains to search for its prey.

"But once it was on a thermal, it could easily rise up a mile or two without any flapping of its wings -- a free ride, just circling. Then at the top, the bird could simply glide to the next thermal and in this way it could certainly travel 200 miles a day," Chatterjee explained.

But how did this huge bird become airborne in the first place?

"The hardest part would be taking off from the ground," observed Chatterjee. "It would have been impossible to take off from a standing start."

The bird probably used some of the same techniques used by modern-day hang-glider pilots such as running on sloping ground to get thrust or energy, or running with a headwind.

Analysis of the region's ancient climate suggests that thermals were present on most days. Thus, the bird probably spent most of its time gliding and foraging for prey, such as rabbit-sized mammals, which it would have swallowed whole with its formidable beak.

"Its jaw mechanics were not suited for tearing flesh from carcasses, as in vultures, nor for tearing prey animals apart for swallowing, as in eagles and owls," said co-author Kenneth Campbell, of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County.

Argentavis is a member of the extinct bird family Teratornithidae within the avian order, Accipitriformes, which is a predatory group of birds related to storks and New World vultures.

The great kori bustard, Ardeotis tardi, is the heaviest modern flying bird weighing approximately 40-pounds (18-kilograms) and the wandering albatross, Diomedea exulans, has the longest wingspan at over 10-feet (3-meters).

The study appears in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Sources

National Geographic (quotes)

BBCNews (quotes, graphic)

Yahoo (quotes)

- Log in to post comments

Perhaps it rarely landed at all; except on high cliffs or trees. Like a sea eagle it might have picked its prey up without landing at all? Just a thought.

It'ld be impressive to see a live one, Golden eagles are impressive but they're titchy compared to this.

Thanks.

I have a problem with the "rabbits and hares" sentence in this really interesting article, as they did not live in Argentina during the Miocene. There were unrelated South American rodents then, somewhat like maras of today, looking a bit like hares and rabbits.

chris, my guess is that this bird was a cliff nesting bird, so that solved one problem it had with becoming air-borne, but yes, it is possible that the bird rarely touched down and instead snatched up its prey while in flight.

thanks dear kitty, i fixed that little error.

I'm so glad you covered this. I ran across these guys once when I was looking for an answer to "what's the heaviest animal able to fly"...and oh my, Teratorns are just teh coolest.

I'm wondering if the air pressure back then would help with lift on the bird. Would 2+ pressures help with getting and staying in the air? Has anyone checked about this possibility?

My guess research is plainly wrong. Poor Argentavis would starve to death, trying to find charitable prey which would overlook it's 11 m wings and let itself be plucked without landing.

I am more inclined to believe that biomechanists were wrong again, and Argentavis was good at takeoff in any way.

The wing of Argentavis is known from a partial humerus only, the regressions used to calculate its body mass and proportions are outdated, and the flight model is based on helicopter design. Seriously, this is functional morphology at its worst - I have no idea why PNAS decided to publish this.

A friend pointed out a little detail in Fig. 4C of the paper. It was too good for me not to blog about.

Bob

ive seen a bird like this of the west coast of tasmania 17 years ago on a cray boat within 20km of the coast. The one i saw was twice as big as a wondering albatros and looked like a brindel diveing bird.Every other bird in the area took of and after landing like a water plain it went to.without a photo wurst luck?MATT

I belive this is a fake because the dimensions are wrong and what is it held up with? I doubt the tail feathers are strong enough to support it standing up like that.

Also the head seems...flat... Like the entire thing is paper.

...matt..............................................................................................................

ive seen a bird like this of the west coast of tasmania 17 years ago on a cray boat within 20km of the coast. The one i saw was twice as big as a wondering albatros and looked like a brindel diveing bird.Every other bird in the area took of and after landing like a water plain it went to.without a photo wurst luck?MATT

............................................................

i am in tasmania

which part of tasie was this

This is probally true. There are many stories on people have had esperiences with large black birds,bigger then a human trying to pick them up off the ground. And actually getting children a couple feet of the ground. If anything they are very rare and probally are cliff dwelling birds so they are rarly seen. Also to the guy who said it is a hoax if you look at the pic closely there are people in the back holding the bird up. Most likly six which is possable.

kenji,

next time, please read the article, then place your comment. as toled, this magnificent creature lived about six million years ago. The picture only shows, how the bird possibly looked like. At least, how people back than thought it would have looked like.

dearkitty,

The article mentioned "rabbit-sized mammals" and said nothing regarding the specifics of "rabbits and hares". Just thought you should know before you go concocting some crazy ideas or something. Hahaha. I'm sure I'm too late by now though.

:)

JP: Maybe it's because the error was fixed by the Grrl?

Maybe the world was much windier back then... Lots of wind = bigger birds.

WE WOULD NOT HAVE NEEDED AEROPLANES.WE WOULD HAVE CULTIVATED THEM LIKE DAIRY COWS AND IT WOULD HAVE BEEN FUN

I saw a bird exactly like this picture except not as large - but it was huge and it was totally black with the head like an Eagle - not a condor. Friday, March 19, 2010 at 11 a.m. It flew over at about 50 feet in a straight line from Superstition Mountain headed to Eagle Rock which is in Gold Canyon, Arizona at the ending point of Mountain Brook Drive. I heard it for seven seconds before I saw it. The sound of those wings sweeping were UNBELIEVABLE. Our black cat was in the yard with us so I assume the bird was on a Recon flyover before trying a snatch. I've never seen a bird this big before. The image on this page is the only one which comes close to describing what I saw. This is not a joke. I just wish I could have gotten a picture of it. Needless to say we're much more restrictive with our cat being outdoors now.