tags: ravens, intelligence, behavior, birds, ornithology

Some of you know that Bernd Heinrich has spent many winters studying ravens and their behavior. This month, Heinrich and his colleague, Thomas Bugnyar, published an article in Scientific American that explores the intelligence of ravens. In this article, they investigate the question; do the birds consciously contemplate alternative behaviors and choose the most appropriate ones, or are they merely relying on instinct or learning to perform specific actions by rote?

They begin by noting that ravens are not the only birds that are reputed to behave intelligently. They state that other relatives of the ravens -- the corvids, such as crows, jays, magpies and nutcrackers -- appear to possess surprising and sophisticated mental abilities. They even mention that these birds' capacities appear to be equivalent to or to even surpass those of the great apes. For example, nutcrackers have the capacity to recall thousands of locations where they have cached food items -- a capacity that exceeds that of humans.

They begin by noting that ravens are not the only birds that are reputed to behave intelligently. They state that other relatives of the ravens -- the corvids, such as crows, jays, magpies and nutcrackers -- appear to possess surprising and sophisticated mental abilities. They even mention that these birds' capacities appear to be equivalent to or to even surpass those of the great apes. For example, nutcrackers have the capacity to recall thousands of locations where they have cached food items -- a capacity that exceeds that of humans.

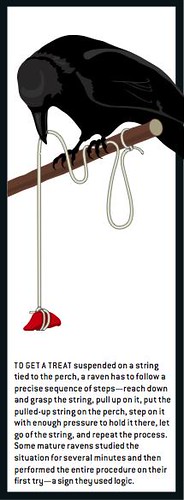

Which leads us to ask; do corvids rely on logic to solve problems or are they relying on instinct? Do corvids distinguish between each other and alter their behaviors accordingly? To more precisely determine the mental capacities of ravens, the largest of the corvids, Heinrich and Bugnyar designed several tests. The first experiment consisted of food hanging from a string below the bottom of the wire cage (pictured right, bigger). To get this treat, the bird had to reach down from a perch and grasp the string in its beak, pull up on the string, place the loop of string on the perch, step on this looped segment of string to prevent it from slipping down, then let go of the string and reach down again and repeat its actions until the morsel of food was within reach.

They found that some adult birds would examine the situation for several minutes and then perform this multistep procedure in as little as 30 seconds without any trial and error -- as if they knew exactly what they were doing. Because there was no opportunity for the birds to be confronted with a similar problem in the wild, the simplest explanation is that they were able to imagine the possibilities and to perform the appropriate behaviors. The authors also found that successfully performing this behavior required maturity: immature birds were unable to do it while year-old birds performed a variety of trials before they were able to succeed.

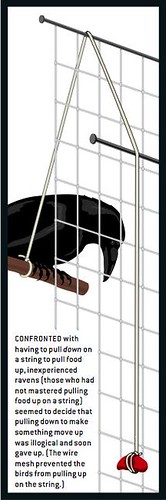

But was it logic that the birds relied on to solve this problem? The authors assert that, basically, knowing how to do something requires few or no trials, whereas trial-and-error learning requires no logic. In fact, it was possible that the birds were rewarded by having the meat become closer with each looping behavior. So as a result, the authors designed another experiment to find out how the birds were solving the problem by presenting them with a situation that was not immediately rewarding because it was counter-intuitive: a string that must be pulled down to cause the food to move upwards towards the bird (pictured left, bigger).

But was it logic that the birds relied on to solve this problem? The authors assert that, basically, knowing how to do something requires few or no trials, whereas trial-and-error learning requires no logic. In fact, it was possible that the birds were rewarded by having the meat become closer with each looping behavior. So as a result, the authors designed another experiment to find out how the birds were solving the problem by presenting them with a situation that was not immediately rewarding because it was counter-intuitive: a string that must be pulled down to cause the food to move upwards towards the bird (pictured left, bigger).

In this situation, the ravens were still interested in the food but none of them managed to solve the problem of obtaining it even though they would have had to use the same sequence of actions. The authors concluded that the pull-up method of obtaining the meat was mastered quickly because it was logical -- a capacity that is lacking or present only to a limited extent in most animals.

Thinking and logic can be quite unreliable and can cause their own set of problems. For example, paper wasps rely on precise hard-wired behaviors to manufacture paper into a nest with a very precise architecture. No learning is required to create the nest, although the environment can modify some genetically programmed behaviors. So why are corvids different? What is special about their social environment that favored the evolved of intelligence as the source for complex behaviors?

Much of the natural history of ravens suggests that they evolved under circumstances that required them to cope with rapidly changing short-term situations. These birds are opportunists who do some hunting on their own, but are mainly dependent upon food that other animals have killed. The predators that inadvertently provide the birds with food are unpredictable and thus, can also kill ravens. Under these circumstances, trial-and-error is evolutionarily untenable because the first mistake in dealing with an unpredictable predator could cost the birds their lives.

Food bonanzas provided by mammalian carnivores are often quickly consumed by them. As a result, it pays ravens to get an early start in feeding -- often, side-by-side with these carnivores. To do this, the birds must be able to predict the carnivores' behavior, such as when they might attack, how far they can jump and how to distract them, and some of that knowledge needs to be in place before the bird itself is distracted by feeding.

Juvenile birds learn these things early in life by interacting with the predators through testing their reactions. Juvenile ravens often will land nearby and nip them from behind. This so-called risky "play activity" is dangerous but ultimately aids in the birds' survival by providing information about the capabilities of various predators. By deliberately provoking them, ravens learn which animals they can trust and how far away they must stay to remain safe.

Ravens also cache food -- busily hauling it away, burying it in secret locations and eating it later. Because ravens have a nearly nonexistent sense of smell, they must memorize the precise location of this stored food, as is the case for other birds that also engage in caching. However, unlike most other caching birds, ravens observe caching of their competitors and thereby memorize the precise locations of not only their own caches, but also those of their competitors. Because of this, ravens prefer to cache their food in private.

As newly-fledged birds that are still being fed by their parents, young ravens practice caching by hiding inedible items. Not only are the young birds learning which items are edible, but equally important, they were also learning to predict their siblings' behavior -- namely, cache pilfering. To better understand practice caching and pilfering behavior, the authors acted as surrogate parents to several young birds. One person was designated the "thief" and always stole a young bird's cache, whereas the other person consistently examined the young birds' caches but never pilfered them.

When the thief was nearby, the authors found that the young birds significantly delayed the time they waited until they cached their food, and they relocated those caches they previously made. In contrast, the presence of the nonthief did not elicit these behaviors. These experiments reveal that the young birds improved their food-caching skills after others raided them, but they also learned to distinguish individuals, in this case, human thieves from human nonthieves.

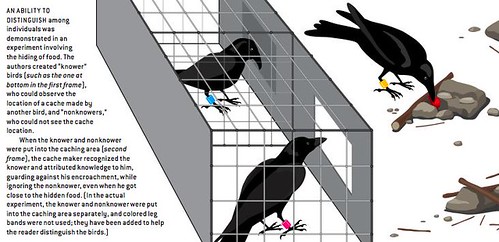

Because wild ravens typically feed in groups, it is nearly impossible for them to cache food without another bird catching them in the act, thereby learning the cache's precise location. Thus, it is important that ravens identify individual birds, just as they are able to distinguish between humans. So the authors designed another experiment where they tested this ability in ravens.

A large aviary was designed for caching. Inside a smaller cage within this aviary were two ravens; one was a "knower" bird that was able to observe the test bird's cache locations, and the other was a "nonknower" bird that had not observed the test subject's caching behavior. The cacher was allowed to make three caches and then that bird was removed from the aviary. Within five minutes after the termination of the caching behavior and the removal of the cacher, either the knower and nonknower birds were allowed to go into the caching arena to search for food.

Knowing that caching birds often retrieve their food when robbery seems imminent, the authors tested the caching birds' behavior when they were in the arena privately, when the nonknower bird was present, or when the knower bird was present in the aviary. They found that the caching bird retrieved its food stores more often when the knower bird came within two meters of the cache. Thus, the authors speculated, the caching bird was able to identify which bird had observed it making its caches and was able to discriminate between it and the "nonknower" bird.

The authors also found that the knower birds were careful about their intentions; they did not go to the caches when the caching birds were nearby, but instead, they waited until they were at some distance. This suggests that both birds had the ability to attribute knowledge to specific individuals and to anticipate a particular response.

The authors used another version of this same experiment to determine if the caching birds made subtle cues that the knower birds might be able to decipher. To do this, a human make the caches, and then stood by passively while either two knower birds, or a knower and a nonknower bird were placed in the aviary together. As predicted, the knower birds were quick to pilfer human-made caches when paired with another knower. However, when paired with a nonknower, the knower bird's reactions depended upon social rank. When a knower was paired with a socially dominant nonknower bird, the knower would delay approaching the cache -- instead, waiting until the dominant bird was some distance away before pilfering the stash. Thus, the authors concluded that it was unlikely that the knowers were providing some behavioral cue that cache raiders might use.

In conclusion, the results of the string-pulling experiment indicate that ravens rely on logic to guide their actions. The results of the pilfer anti-pilfer experiments show that ravens react to their competitors based on what they remember them being able to observe, that they can accurately attribute the capacity of knowledge to their competitors, and that they integrate this knowledge together with social status to make strategic decisions when retrieving food caches.

- Log in to post comments

Yes, but have they figured out how to open doors like their Cretaceous ancestors? ;)

Seriously, though, that rocks! Birds are awesome!

I'm a little disappointed that ravens don't seem capable of understanding the principle of a pulley...but on the whole, a very nice article, and some very cool data on bird behavior.

Even though I enjoy David Attenborough's The Life of Birds, ravens are still number one for me.

One day I was off work early and stopped at Starbucks on the way home, arriving an hour ahead of my usual time. I noticed a dozen ravens high up in a tree, not really doing anything. Minutes later, when I came out with my drink, the tree now held about fifty ravens, and they were all facing to my left. Looking that way, I saw nothing even remotely conceivable as a threat, so I was dumfounded, just standing there watching. A moment later, the sprinklers to my left went off, and the whole treeful of ravens took to wing, descending to the freshly soaked lawn, where they began feeding on the worms and insects that had been driven to the surface. Yet people with wristwatches have trouble making their meetings on time.

A friend was jogging down an alley when he saw a raven atop the distant corner of a roof take notice of him. The bird watched him jog closer, then squawked at him and shook its wings. It then looked down behind itself at whatever lay around the corner was approaching. The bird kept squawking and flapping at him, and looking down behind the building. The man became certain the bird was warning him not to reach the corner. When he rounded the corner, there was a big dog, and the raven was looking down at him and the dog. When my friend told me this story, not expecting me to believe it, I found it utterly credible. Ravens are not alone in the strategy of ruining a predator's opportunities in order to encourage the animal to look for a less unlucky territory.

I live in Alhambra in Los Angeles County. The older neighborhoods have a lot of live oaks, and many of the ravens here know about dropping acorns from heights onto hard pavement, and about putting hard nuts at stoplights.

I have heard people claim birds that cache thousands of seeds remember every one of them, but I personally doubt this. The researcher would have to note every seed hidden by a bird to find out if the bird remembered every single one, or instead relied on a strategy. If the bird caches in places it recognizes as 'this looks like my kind of hiding spot' then he would only need to look at nearby likely areas to find high-yield targets to search. Similarly, if you were a raven, wouldn't it be smarter to study your victim's habits so that you can recognize likely caches of his and of others of his species?

Nice to see some corvid news. My favorite corvid picture involved some predator teasing that went a bit wrong. A group of crows was teasing some eagles at a kill, pulling their tail feathers and such. From the ground, crows can easily evade eagles. But one of the eagles somehow got a drop on one of the crows, though and came after it -- the photographer got a great picture of an eagle with talons open very close to one very scared looking crow (beak wide open) mid-flight. The eagle was just teaching the crow a lesson and didn't take it, but I suspect that at least one crow stopped teasing eagles for a bit. The picture was here:

http://www.mikeblairoutdoors.com/mikeblair/outdoor_quill/eagle_joust

It's down for now.

Hi Roy,

I do not understand your reasoning regarding the raven warning the man. Why would a raven want to discourage a predator when it relies on them? Wouldn't it have been best for the raven if either mammal had killed the other?

Carsten

P.S.: I have read 1.5 books on biology, both by Heinrich, one about ravens, the other one "Why we run".

We recently discussed this article in an animal behavior discussion group. Some of the feats accomplished by Corvids really seem to indicate some sort of metacognition, or consciousness. But in any of these amazing animal stories, (such as Betty the Raven, or Alex the Parrot) it seems as though they don't really generalize to the species. Our groups main concerns came from the over-anthropomorphism and the idea that exceptional behavior like this doesn't necessarily equate to consciousness. In fact the only thing missing from the following video is a Bob Saget voice-over and some wacky sound effects:

Here is a video of Betty

Thank you so much for sharing this with us. I too find animal intelligence fascinating. Learning that ravens can use logic really made my day!

I think the pulley issue is actually revealing something interesting. I wouldn't say that the birds were necessarily using "logic", so much as matching the task to their repertoire of motor techniques.

To give a domestic example, I often exercise my cat with dangly toys at the end of a long wand. She clearly understands the idea of stepping on the toy or string (once captured) to keep it put while she chews on it. I suspect she's extended that to holding the toy "hostage" until I pet her for a bit.

She has not however, learned to grab the hanging string in order to capture the toy. That wouldn't occur to her, because she "knows" how to "catch the birdie" -- bite or swipe at the moving object. Likewise, I suspect that the older ravens had better chances of having been "primed" with situations involving both pulling "strings" (worms?), and stepping on things to keep them put, both likely candidates for prepared learning. But natural pulleys are not so common, so none of the birds had occasion to try such things, nor prepared learning to assist them.

I grew up in the Yukon, and have a great fondness for our Territorial Bird (http://www.gov.yk.ca/yukonglance/bird.html).

Two examples certainly show that they are probably smarter than your average bear.

Ravens will tag-team domestic dogs in order to steal their food; taking turns to distract the dog, while the other steals the food. Also, ravens have learned to sit on the photocells of the traffic lights in order to turn the lights on during the day to keep their feet warm.

Adam

Carsten,

I agree about the Raven warning. In fact in Heinrich's Raven book, he expressed the opinion that a raven in a similar situation was trying to alert a predator to the presence of potential prey (a mountain lion and a hiker IIRC.) Seems to me that violent confrontations benefit the scavenger.

Perhaps the Raven considered the man the hunter and wished him to eat the dog. If Ravens are that smart then they most likely have ascertained man's position in the food-chain.

Don't forget the New Caledonian Crow, which makes and uses different types of tools for extracting grubs out of logs.

I've seen where Ravens will operate zippers to access the pocket contents of an untended backpack. What really amuses me is to watch them on the road far ahead, pecking away at roadkill, all the while swivelling their heads, scanning left and right, watching for predators (cars)....instead of flying away, though, when I drive past, they hop off to the shoulder and then hop back in my rearview mirror. Now I understand why.

One time I saw where somebody left a 50-lb bag of dog kibbles in the bed of their truck, and it was like a raven party of probably two dozen birds there, and they'd torn open the bag and were all going crazy...

David, about your cat... maybe it is just your cat? Playing that game with my cat is very dangerous because he sometimes prefers to actually go for the the stick that holds the string or the string itself. He usually stops and studies the situation a bit beforehand, so I have a bit of a warning.

bernd heinrich steals raven babies form parents.

Roy,

I appreciated your comments about Corvid caching ability. In fact, researchers who have studied this do not claim that these birds can recover every single food item, but they can recover a large majority of cached seeds. However, at least in pinyon jays, nutcrackers and Aphelocoma jays, these studies did involve researchers noting the location of every single seed the birds cached, as these experiments were performed in a laboratory setting. Birds cached in large rooms with floors full of sand-filled Dixie cups.

Your 'my kind of hiding spot' idea is a good one, where birds use what is known as a rule - always caching to the north of large rocks or trees, for example. However, experimental work has shown that this isn't what happens, at least in nutcrackers. They use landscape cues to remember where they made each and every cache. Amazing, isn't it?

I tried the pulley experiment on my pair of Moluccan cockatoos. I tied an almond to the end of a string and then tied the string to a perch as shown in the illustration.

Herman, aka Destructo-Too, looked at the almond, looked at the string, looked at the knot, then chewed through the string at the knot and the almond fell to the floor.

Sunshine looked at the almond, and then looked at me and said, "Mom, give me that almond. RIGHT NOW! AND I MEAN IT!"

When I told her she had to figure out how to get it herself, she just said, "NO! Give it to me."

David, about your cat... maybe it is just your cat?

In the details, probably so! My point was just that her reponses were stereotyped, and more limited than was obvious. In fact, she often does happen to catch the string with her paws, but she doesn't use that as a tactic. I've also noted that she responds much more eagerly when I get the lure to make noise. She doesn't jump at the stick, but I suspect she's just too fat to jump that high. (Which is why I've been trying to exercise her more!)

On the other hand, I had to give up on my pen-laser as a cat toy, for the very reason you describe -- Gremlin quickly (~30 minutes the first time) noticed that there was another red "bug" in my hand, and that one didn't run away as fast!

Parrotslave: Sounds like Herman went for his preferred treat, while Sunshine has her own strategy.... ;-)

I, too, have noticed that crows seem to be pretty smart when it comes to cars. They almost never wait too late to move away from an approaching car, and almost always move just enough to avoid being hit.

I wonder what the raven would have done with the pulley experiment if the experimenter had somehow demonstrated that pulling the string down would bring the prize up.

Nice post Grrl. I also wrote something about corvid intelligence.

Not a single "nevermore" joke in the article or the comments? I'm disappointed.

are they smarter than border collies? my bc catches ravens - she creeps up from the flank and they fly into her mouth. bad dog!

Years ago when I lived in California's Eastern Sierra, I saw two ravens doing something interesting. There's a water tank for overheated radiators halfway up a 9-mile grade on Highway 395 between Bishop and Tom's place. The cylindrical tank has a spout on the end, with a simple press-down handle to release water. As I approached the tank pullout one hot summer day, I could see some kind of motion at that end of the tank. As I got closer, I could see clearly what was happening: a raven stood with its weight on the push handle, fluttering for balance, and on the pavement just below, another raven fluttered and fluffed his feathers in the outflow of water.

It was a little bit of magic, and I like to hopefully think they were smart enough to be doing it deliberately, and that they switched off after a few minutes.

3 corvid stories.

one day, a neighbor came to my window and told me that there was a flock of magpies in the trees around my house, making a lot of noise. i went out, confirmed, then climbed to the roof. on the roof was a dead magpie. i removed it and the noise escalated. nothing unusual there, but for the next 2 or 3 days, the flock returned and squawked over the site. memory and grieving?

an almost identical story: this time is was leaving for work and heard a commotion. around the corner, a flock of magpies was perched in a tree squawking at an injured magpie on the ground (its wishbone had separated and was protruding from its chest). i left matters be and went to work. when i came home, the injured bird was still there and so were the flock. were they protecting the injured one? in any case, these observations indicate a strong sense of community.

but they can also be stupid... once, in a park i was playing with my daughter under a tree. in the tree, there were 3 crows, 1 large and 2 smaller. the smaller ones were hopping around, apparently trying to impress the larger (courtship?). suddenly, the two charged each other and tumbled out of the tree a few feet from me. i walked over to them. each had a claw around the throat of the other and neither would let go! they looked up at me but did nothing. i could have nudged them with my feet. i left them alone. a few minutes later, the big one flew away. you could almost sense her disdain.

I would like to clarify that it is not exactly true that none of the ravens were able to solve the pulley problem: none of the ravens who had never been presented any sort of string problem before were able to solve the pulley problem. The ravens who had previously solved the regular pull-up problem were all subsequently able to get the meat in the pulley situation.

The paper they published about these experiments is well worth reading: [Bernd Heinrich, Thomas Bugnyar (2005) Testing Problem Solving in Ravens: String-Pulling to Reach Food Ethology 111 (10), 962-976.](available at http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1439-0310.2005.01133… if you have access through a college or similar arrangement).

Another interesting thing that can be seen in the paper is that apparently there is a fairly wide intelligence distribution in ravens. Of the six individuals tested in the pull-up task, five of them were able to solve it. A table recording the number of interactions until the solution was reached or the experiment was terminated lists interactions by type: flying at meat, pecking at string, etc. Five individuals solved the problem with 10-47 interactions total.

The sixth individual, labeled 'Y', failed. Looking at the table it's clear why: he's obviously the raven equivalent of an idiot. He had 253 interactions, 214 of which were flying at the meat, the dumbest action possible. While the other five ravens later solved the pulley problem, Y tried to reach the meat by "crowding up to the wire" (he failed).

Number of interactions are also listed for the pulley experiment: for the naive ravens (the ravens who had not previously been tested in the pull-up task, five total), three had zero interactions total. No flying at the wire, pecking at the string, nothing. One had one interaction ("flying at wire"). The other two had 14 and 28, consisting mostly of "handling string".

Nonetheless, the paper reports that they all "visually inspected the experimental set-up of the pull-down task intensively". From my perspective, what happened is obvious: they looked at the setup, decided it was too much trouble, and decided that it would be easier to wait until tomorrow to be fed, the slackers.

Finally, it's interesting how little time in general the ravens had to solve the problems. For the pulley problem in particular, they were given each only three 15 minute sessions, for 45 minutes total. The naive ravens gave up after at most seven minutes (3 minutes median).

Such are the pitfalls of such small sample sizes: one group had a particularly dumb raven, and the other group was unmotivated.

I think therefore I am or...

I have a large brain SO I think therefore I am...

Perhaps the biggest cognitive difference between us and ravens is vocal chords. I am sure you have come across this before but it continually fascinates me...

http://www.flatrock.org.nz/topics/science/is_the_brain_really_necessary…

After a dozen family cats ended up as road kill, it was nice to have one smart enough to look both ways before crossing the street. I'm not sure why we'd gotten the second cat. They generally didn't get along. So, it was with interest that i saw the two of them at the road side. They were both stopped. The older one looked both ways, crossed, stopped, looked both ways, crossed back. The younger one looked both ways, and crossed.

The sample size is small. But there's no way to interpret the events other than as teacher and pupil. There are other examples with this pair.

It is my impression that lots of animals are very smart, emotional, self aware, aware of others, etc. Some of these are humans.