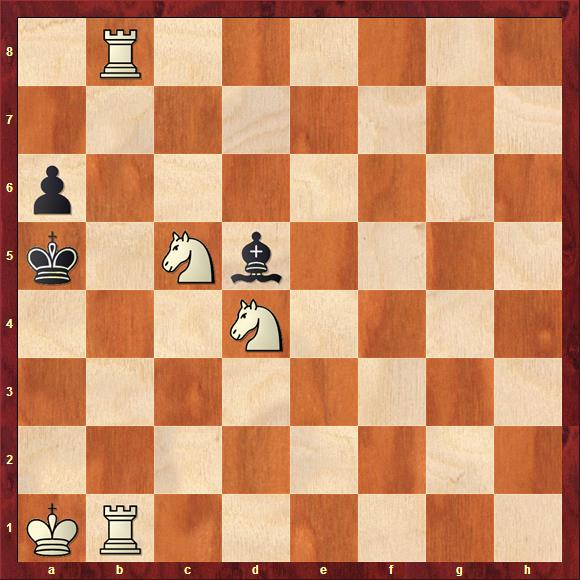

Some chess problems are engineering marvels featuring deep and complex strategy. Other problems are elegant and delightful, and serve as reminders of just how much play can be squeezed out of a small number of pieces. This week's problem is of the latter sort. It was composed by Normal Macleod in 1962. The position below calls for white to play and mate in two:

Let's consider white's options. The move 1. Nd6 looks strong.

This doesn't threaten anything immediately, but the knight is eyeing the squares b7 and c4. Black has to move his bishop. Moving it along the a2-g8 diagonal leaves b7 uncovered and allows 2. Nb7 mate. Moving the bishop along the a8-h1 diagonal leaves c4 unguarded and allows 2. Nc4 mate.

It's looking bad for black, but not so fast. Black can play 1. ... Bb3. Yes, this leaves b7 unguarded. But it also cuts off one of the white rooks. If white tries 2. Nb7 now, it will cut off the other rook and allow the black king to escape to the b file.

This sort of thing is known as a correction move. A random black move along a line commits an error that white can exploit (in this case it unguards a square). But a strategically chosen black move negates the error with some compensating advantage (in this case it interferes with a white piece.)

So, white was unsuccessful. 1. Nd6 was a good try, but it does not work. Let's move on. How about 1. Nd4?

Now white is eyeing the c6 and b3 squares. Any move by the black bishop will unguard one of these squares. But this time black has 1. ... Bb7. This maintains the guard on c6. It also defeats the potential mate on b3 by again cutting off one of the white rooks. Drat!

But now we might suspect the key move. White plays 1. Nc3!

This works! White is now looing at mates on b3 and b7. Random moves by the black bishop release one of these squares, permitting mate. But this time his little interference trick does not work. If the black bishop tries to interfere on b3 or b7, white is not forced to cut off the other rook. He can just take the bishop!

Very nice! Now, here's some more problem jargon for you. This is a three-phase problem, since it has two tries and a key. In each phase, the manner in which white addresses random bishop moves changes. This sort of arrangement is known as a Zagoruyko, after the great Russian composer who devised many ingenious variations on this idea. More precisely, it is a three-by-two Zagoruyko, since it features changed mates to two defenses over three phases. That this can be achieved with just eight pieces, with interesting strategy, is impressive.

One other constructional point. Normally it would be considered a weakness to have a key that moves an attacked white piece to safety. A good key should be counter-intuitive. It should not obviously help white, and it's even better if at first glance it seems to hurt white. In this case, though, the weakness is mitigated by the fact that there is a set mate for the knight capture. Black capturing the knight is such an obviously strong move that if there were no set mate the solver would immediately have a huge hint towards the key. He would know he must find a move that gives white a continuation for that strong defense. So, in this case the key is not ideal, but it is not bad either.

See you next week!

- Log in to post comments

Interesting.

My approach to this problem was to observe that Black's king was blocked along the b file by (potentially) both rooks, and from the a4 square by the knight on c5. This immediately suggests that the knight on b5 is the key piece. When you see that, it again immediately suggests to me that since the b-file is covered by both rooks, it would be worth seeing if it is worth covering the a4 square with both knights, which leads to the Nc3 key move.

In this way I did not even seriously consider the two 'failed' attempts you describe above, though obviously had Nc3 not been the key move those would have been considered.

A splendid explanation of the problem, Jason. And a fine explication of the logical approach to problem-solving by Gazza.

My approach was rather more, ummm.... intuitive. Or perhaps I should say, "human".

I INSTANTLY spotted the winner 1.Nd6, and just as instantly congratulated myself & compared myself somewhat favorably to Komodo. I reached for the mouse to scroll down to reap the rewards of reading through the solution.

Simultaneously, certain thoughts were hydroplaning along in my allegedly conscious self. Such as: "Bill, do you really think Jason would post such an easy one?' And: "Yes, Bill, the bishop does have to move -- but have you really LOOKED AT each square it could move to?"

And as soon as I saw the second sentence "The move 1.Nd6 looks strong," I knew. I imagine my chest sagged a bit.

Ahh, the joy of problem-solving.

Movie alert:

The Dark Horse

Opening April 1, 2016